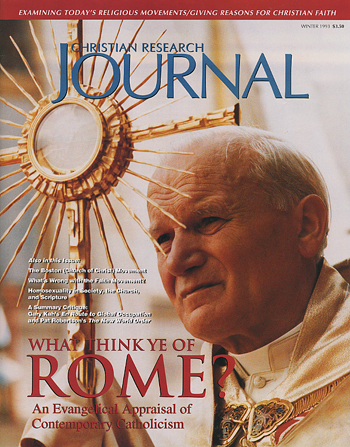

What Think Ye of Rome? (1994)

WHAT THINK YE OF ROME? (Part Three): The Catholic‐Protestant Debate on Biblical Authority

WHAT THINK YE OF ROME? (Part Four): The Catholic‐Protestant Debate on Papal Infallibility

WHAT THINK YE OF ROME? (Part Five): The Catholic‐Protestant Debate on Justification

Summary

Traditional Roman Catholicism has always, in its official pronouncements, held sacred Scripture in high esteem. Indeed, doctors of the church such as Jerome, Augustine, Anselm, and Aquinas — when dealing with Holy Writ — at times sound positively Protestant. Unfortunately, Roman Catholicism has not followed their lead and has elevated extrabiblical tradition to the same level as the Bible. The authors maintain this is a serious error, having dire consequences on the practical formation of the laypersonʹs Christian faith. Scripture itself should be the final authoritative guide for the Christian. As the apostle Paul reminds Timothy, ʺFrom infancy you have known [the] sacred scriptures, which are capable of giving you wisdom for salvation through faith in Christ Jesusʺ (2 Tim. 3:15 [The New American Bible]).

How should evangelical Protestants view contemporary Roman Catholicism? In the first two installments of this series1 Kenneth R. Samples showed that classic Catholicism and Protestantism are in agreement on the most crucial doctrines of the Christian faith, as stated in the ancient ecumenical creeds. Nonetheless, he also outlined five doctrinal areas that separate Roman Catholics from evangelical Protestants: authority, justification, Mariology, sacramentalism and the mass, and religious pluralism.

Samples observed that Roman Catholicism is foundationally orthodox, but it has built much on this foundation that tends to compromise and undermine it. He concluded that Catholicism should therefore be viewed as ʺneither a cult (non‐Christian religious system) nor a biblically sound church, but a historically Christian church which is in desperate need of biblical reform.ʺ

With the first two installments of this series being largely devoted to establishing that Catholicism is a historic Christian church, it is appropriate that in the remaining installments we turn our attention to the most critical doctrinal differences between Catholics and Protestants. This is especially important at a time when many ecumenically minded Protestants are ready to portray the differences between Catholics and Protestants as little more important than the differences that separate the many Protestant denominations. For although the doctrinal differences between Catholics and Protestants do not justify one side labeling the other a cult, they do justify the formal separation between the two camps that began with the 16th‐century Protestant Reformation and that continues today.

Among the many doctrinal differences between Catholics and Protestants, none are more fundamental than those of authority and justification. In relation to these the Protestant Reformation stressed two principles: a formal principle (sola Scriptura) and a material principle (sola fide)2: The Bible alone and faith alone. In this installment and in Part Four we will focus on the formal cause of the Reformation, authority. In the concluding installment, Part Five, we will examine its material cause, justification.

PROTESTANT UNDERSTANDING OF SOLA SCRIPTURA

By sola Scriptura Protestants mean that Scripture alone is the primary and absolute source for all doctrine and practice (faith and morals). Sola Scriptura implies several things. First, the Bible is a direct revelation from God. As such, it has divine authority. For what the Bible says, God says.

Second, the Bible is sufficient: it is all that is necessary for faith and practice. For Protestants ʺthe Bible aloneʺ means ʺthe Bible onlyʺ is the final authority for our faith.

Third, the Scriptures not only have sufficiency but they also possess final authority. They are the final court of appeal on all doctrinal and moral matters. However good they may be in giving guidance, all the fathers, Popes, and Councils are fallible. Only the Bible is infallible.

Fourth, the Bible is perspicuous (clear). The perspicuity of Scripture does not mean that everything in the Bible is perfectly clear, but rather the essential teachings are. Popularly put, in the Bible the main things are the plain things, and the plain things are the main things. This does not mean — as Catholics often assume — that Protestants obtain no help from the fathers and early Councils. Indeed, Protestants accept the great theological and Christological pronouncements of the first four ecumenical Councils. What is more, most Protestants have high regard for the teachings of the early fathers, though obviously they do not believe they are infallible. So this is not to say there is no usefulness to Christian tradition, but only that it is of secondary importance.

Fifth, Scripture interprets Scripture. This is known as the analogy of faith principle. When we have difficulty in understanding an unclear text of Scripture, we turn to other biblical texts. For the Bible is the best interpreter of the Bible. In the Scriptures, clear texts should be used to interpret the unclear ones.

CATHOLIC ARGUMENTS FOR THE BIBLE PLUS TRADITION

One of the basic differences between Catholics and Protestants is over whether the Bible alone is the sufficient and final authority for faith and practice, or the Bible plus extrabiblical apostolic tradition. Catholics further insist that there is a need for a teaching magisterium (i.e., the Pope and their bishops) to rule on just what is and is not authentic apostolic tradition.

Catholics are not all agreed on their understanding of the relation of tradition to Scripture. Some understand it as two sources of revelation. Others understand apostolic tradition as a lesser form of revelation. Still others view this tradition in an almost Protestant way, namely, as merely an interpretation of revelation (albeit, an infallible one) which is found only in the Bible. Traditional Catholics, such as Ludwig Ott and Henry Denzinger, tend to be in the first category and more modern Catholics, such as John Henry Newman and Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, in the latter. The language of the Council of Trent seems to favor the traditional understanding.3

Whether or not extrabiblical apostolic tradition is considered a second source of revelation, there is no question that the Roman Catholic church holds that apostolic tradition is both authoritative and infallible. It is to this point that we speak now.

The Catholic Argument for Holding the Infallibility of Apostolic Tradition

The Council of Trent emphatically proclaimed that the Bible alone is not sufficient for faith and morals. God has ordained tradition in addition to the Bible to faithfully guide the church.

Infallible guidance in interpreting the Bible comes from the church. One of the criteria used to determine this is the ʺunanimous consent of the Fathers.ʺ4 In accordance with ʺThe Profession of Faith of the Council of Trentʺ (Nov. 13, 1565), all faithful Catholics must agree: ʺI shall never accept nor interpret it [ʹHoly Scriptureʹ] otherwise than in accordance with the unanimous consent of the Fathers.ʺ5

Catholic scholars advance several arguments in favor of the Bible and tradition, as opposed to the Bible only, as the final authority. One of their favorite arguments is that the Bible itself does not teach that the Bible only is our final authority for faith and morals. Thus they conclude that even on Protestant grounds there is no reason to accept sola Scriptura. Indeed, they believe it is inconsistent or self‐refuting, since the Bible alone does not teach that the Bible alone is the basis of faith and morals.

In point of fact, argue Catholic theologians, the Bible teaches that apostolic ʺtraditionsʺ as well as the written words of the apostles should be followed. St. Paul exhorted the Thessalonian Christians to ʺstand fast and hold the traditions which you were taught, whether by word or epistleʺ (2 Thess. 2:15; cf. 3:6).

One Catholic apologist even went so far as to argue that the apostle John stated his preference for oral tradition. John wrote: ʺI have much to write to you, but I do not wish to write with pen and ink. Instead, I hope to see you soon when we can talk face to faceʺ (3 John 13). This Catholic writer adds, ʺWhy would the apostle emphasize his preference for oral Tradition over written Tradition…if, as proponents of sola Scriptura assert, Scripture is superior to oral Tradition?ʺ6

Roman Catholic apologist Peter Kreeft lists several arguments against sola Scriptura which in turn are arguments for tradition: ʺFirst, it separates Church and Scripture. But they are one. They are not two rival horses in the authority race, but one rider (the Church) on one horse (Scripture).ʺ He adds, ʺWe are not taught by a teacher without a book or by a book without a teacher, but by one teacher, the Church, with one book, Scripture.ʺ7

Kreeft further argues that ʺsola Scriptura violates the principle of causality; that an effect cannot be greater than its cause.ʺ For ʺthe successors of the apostles, the bishops of the Church, decided on the canon, the list of books to be declared scriptural and infallible.ʺ And ʺif the Scripture is infallible, then its cause, the Church, must also be infallible.ʺ8

According to Kreeft, ʺdenominationalism is an intolerable scandal by scriptural standards — see John 17:20‐23 and I Corinthians 1:10‐17.ʺ But ʺlet five hundred people interpret the Bible without Church authority and there will soon be five hundred denominations.ʺ9 So rejection of authoritative apostolic tradition leads to the unbiblical scandal of denominationalism.

Finally, Kreeft argues that ʺthe first generation of Christians did not have the New Testament, only the Church to teach them.ʺ10 This being the case, using the Bible alone without apostolic tradition was not possible.

A PROTESTANT DEFENSE OF SOLA SCRIPTURA

As convincing as these arguments may seem to a devout Catholic, they are devoid of substance. As we will see, each of the Roman Catholic arguments against the Protestant doctrine of sola Scriptura fails, and they are unable to provide any substantial basis for the Catholic dogma of an infallible oral tradition.

Does the Bible Teach Sola Scriptura?

Two points must be made concerning whether the Bible teaches sola Scriptura. First, as Catholic scholars themselves recognize, it is not necessary that the Bible explicitly and formally teach sola Scriptura in order for this doctrine to be true. Many Christian teachings are a necessary logical deduction of what is clearly taught in the Bible (e.g., the Trinity). Likewise, it is possible that sola Scriptura could be a necessary logical deduction from what is taught in Scripture.

Second, the Bible does teach implicitly and logically, if not formally and explicitly, that the Bible alone is the only infallible basis for faith and practice. This it does in a number of ways. One, the fact that Scripture, without tradition, is said to be ʺGod‐breathedʺ (theopnuestos) and thus by it believers are ʺcompetent, equipped for every good workʺ (2 Tim. 3:16‐17, emphasis added) supports the doctrine of sola Scriptura. This flies in the face of the Catholic claim that the Bible is formally insufficient without the aid of tradition. St. Paul declares that the God‐breathed writings are sufficient. And contrary to some Catholic apologists, limiting this to only the Old Testament will not help the

Catholic cause for two reasons: first, the New Testament is also called ʺScriptureʺ (2 Pet. 3:15‐16; 1 Tim. 5:18; cf. Luke 10:7); second, it is inconsistent to argue that God‐breathed writings in the Old Testament are sufficient, but the inspired writings of the New Testament are not.

Further, Jesus and the apostles constantly appealed to the Bible as the final court of appeal. This they often did by the introductory phrase, ʺIt is written,ʺ which is repeated some 90 times in the New Testament. Jesus used this phrase three times when appealing to Scripture as the final authority in His dispute with Satan (Matt. 4:4, 7, 10).

Of course, Jesus (Matt. 5:22, 28, 31; 28:18) and the apostles (1 Cor. 5:3; 7:12) sometimes referred to their own Godgiven authority. It begs the question, however, for Roman Catholics to claim that this supports their belief that the church of Rome still has infallible authority outside the Bible today. For even they admit that no new revelation is being given today, as it was in apostolic times. In other words, the only reason Jesus and the apostles could appeal to an authority outside the Bible was that God was still giving normative (i.e., standard‐setting) revelation for the faith and morals of believers. This revelation was often first communicated orally before it was finally committed to writing (e.g., 2 Thess. 2:5). Therefore, it is not legitimate to appeal to any oral revelation in New Testament times as proof that nonbiblical infallible authority is in existence today.

What is more, Jesus made it clear that the Bible was in a class of its own, exalted above all tradition. He rebuked the Pharisees for not accepting sola Scriptura and negating the final authority of the Word of God by their religious traditions, saying, ʺAnd why do you break the commandment of God for the sake of your tradition?…You have nullified the word of God, for the sake of your traditionʺ (Matt. 15:3, 6).

It is important to note that Jesus did not limit His statement to mere human traditions but applied it specifically to the traditions of the religious authorities who used their tradition to misinterpret the Scriptures. There is a direct parallel with the religious traditions of Judaism that grew up around (and obscured, even negated) the Scriptures and the Christian traditions that have grown up around (and obscured, even negated) the Scriptures since the first century. Indeed, since Catholic scholars make a comparison between the Old Testament high priesthood and the Roman Catholic papacy, this would seem to be a very good analogy.

Finally, to borrow a phrase from St. Paul, the Bible constantly warns us ʺnot to go beyond what is writtenʺ (1 Cor. 4:6).11 This kind of exhortation is found throughout Scripture. Moses was told, ʺYou shall not add to what I command you nor subtract from itʺ (Deut. 4:2). Solomon reaffirmed this in Proverbs, saying, ʺEvery word of God is tested….Add nothing to his words, lest he reprove you, and you be exposed as a deceiverʺ (Prov. 30:5‐6). Indeed, John closed the last words of the Bible with the same exhortation, declaring: ʺI warn everyone who hears the prophetic words in this book: if anyone adds to them, God will add to him the plagues described in this book, and if anyone takes away from the words in this prophetic book, God will take away his share in the tree of life…ʺ (Rev. 22:18‐19). Sola Scriptura could hardly be stated more emphatically.

Of course, none of these are a prohibition on future revelations. But they do apply to the point of difference between Protestants and Catholics, namely, whether there are any authoritative normative revelations outside those revealed to apostles and prophets and inscripturated in the Bible. And this is precisely what these texts say. Indeed, even the prophet himself was not to add to the revelation God gave him. For prophets were not infallible in everything they said, but only when giving Godʹs revelation to which they were not to add or from which they were not to subtract a word.

Since both Catholics and Protestants agree that there is no new revelation beyond the first century, it would follow that these texts do support the Protestant principle of sola Scriptura. For if there is no normative revelation after the time of the apostles and even the prophets themselves were not to add to the revelations God gave them in the Scriptures, then the Scriptures alone are the only infallible source of divine revelation.

Roman Catholics admit that the New Testament is the only infallible record of apostolic teaching we have from the first century. However, they do not seem to appreciate the significance of this fact as it bears on the Protestant argument for sola Scriptura. For even many early fathers testified to the fact that all apostolic teaching was put in the New Testament. While acknowledging the existence of apostolic tradition, J. D. N. Kelly concluded that ʺadmittedly there is no evidence for beliefs or practices current in the period which were not vouched for in the books later known as the New Testament.ʺ Indeed, many early fathers, including Athanasius, Cyril of Jerusalem, Chrysostom, and Augustine, believed that the Bible was the only infallible basis for all Christian doctrine.12

Further, if the New Testament is the only infallible record of apostolic teaching, then every other record from the first century is fallible. It matters not that Catholics believe that the teaching Magisterium later claims to pronounce some extrabiblical tradition as infallibly true. The fact is that they do not have an infallible record from the first century on which to base such a decision.

All Apostolic ʺTraditionsʺ Are in the Bible

It is true that the New Testament speaks of following the ʺtraditionsʺ (=teachings) of the apostles, whether oral or written. This is because they were living authorities set up by Christ (Matt. 18:18; Acts 2:42; Eph. 2:20). When they died, however, there was no longer a living apostolic authority since only those who were eyewitnesses of the resurrected Christ could have apostolic authority (Acts 1:22; 1 Cor. 9:1). Because the New Testament is the only inspired (infallible) record of what the apostles taught, it follows that since the death of the apostles the only apostolic authority we have is the inspired record of their teaching in the New Testament. That is, all apostolic tradition (teaching) on faith and practice is in the New Testament.

This does not necessarily mean that everything the apostles ever taught is in the New Testament, any more than everything Jesus said is there (cf. John 20:30; 21:25). What it does mean is that all apostolic teaching that God deemed necessary for the faith and practice (morals) of the church was preserved (2 Tim. 3:15‐17). It is only reasonable to infer that God would preserve what He inspired.

The fact that apostles sometimes referred to ʺtraditionsʺ they gave orally as authoritative in no way diminishes the Protestant argument for sola Scriptura. First, it is not necessary to claim that these oral teachings were inspired or infallible, only that they were authoritative. The believers were asked to ʺmaintainʺ them (1 Cor. 11:2) and ʺstand fast in themʺ (2 Thess. 2:15). But oral teachings of the apostles were not called ʺinspiredʺ or ʺunbreakableʺ or the equivalent, unless they were recorded as Scripture.

The apostles were living authorities, but not everything they said was infallible. Catholics understand the difference between authoritative and infallible, since they make the same distinction with regard to noninfallible statements made by the Pope and infallible ex cathedra (ʺfrom the seatʺ of Peter) ones.

Second, the traditions (teachings) of the apostles that were revelations were written down and are inspired and infallible. They comprise the New Testament. What the Catholic must prove, and cannot, is that the God who deemed it so important for the faith and morals of the faithful to inspire the inscripturation of 27 books of apostolic teaching would have left out some important revelation in these books. Indeed, it is not plausible that He would have allowed succeeding generations to struggle and even fight over precisely where this alleged extrabiblical revelation is to be found. So, however authoritative the apostles were by their office, only their inscripturated words are inspired and infallible (2 Tim. 3:16‐17; cf. John 10:35).

There is not a shred of evidence that any of the revelation God gave them to express was not inscripturated by them in the only books — the inspired books of the New Testament — that they left for the church. This leads to another important point.

The Bible makes it clear that God, from the very beginning, desired that His normative revelations be written down and preserved for succeeding generations. ʺMoses then wrote down all the words of the Lordʺ (Exod. 24:4), and his book was preserved in the Ark (Deut. 31:26). Furthermore, ʺJoshua made a covenant with the people that day and made statutes and ordinances for them… which he recorded in the book of the law of Godʺ (Josh. 24:25‐26) along with Mosesʹ (cf. Josh. 1:7). Likewise, ʺSamuel next explained to the people the law of royalty and wrote it in a book, which he placed in the presence of the Lordʺ (1 Sam. 10:25). Isaiah was commanded by the Lord to ʺtake a large cylinderseal, and inscribe on it in ordinary lettersʺ (Isa. 8:1) and to ʺinscribe it in a record; that it may be in future days an eternal witnessʺ (30:8). Daniel had a collection of ʺthe booksʺ of Moses and the prophets right down to his contemporary Jeremiah (Dan. 9:2).

Jesus and New Testament writers used the phrase ʺIt is writtenʺ (cf. Matt. 4:4, 7, 10) over 90 times, stressing the importance of the written word of God. When Jesus rebuked the Jewish leaders it was not because they did not follow the traditions but because they did not ʺunderstand the Scripturesʺ (Matt. 22:29). All of this makes it clear that God intended from the very beginning that His revelation be preserved in Scripture, not in extrabiblical tradition. To claim that the apostles did not write down all Godʹs revelation to them is to claim that they were not obedient to their prophetic commission not to subtract a word from what God revealed to them.

The Bible Does Not State a Preference for Oral Tradition

The Catholic use of 3 John to prove the superiority of oral tradition is a classic example of taking a text out of context. John is not comparing oral and written tradition about the past but a written, as opposed to a personal, communication in the present. Notice carefully what he said: ʺI have much to write to you, but I do not wish to write with pen and ink. Instead, I hope to see you soon when we can talk face to faceʺ (3 John 13). Who would not prefer a face‐to‐face talk with a living apostle over a letter from him? But that is not what oral tradition gives. Rather, it provides an unreliable oral tradition as opposed to an infallible written one. Sola Scriptura contends the latter is preferable.

The Bible Is Clear Apart from Tradition

The Bible has perspicuity apart from any traditions to help us understand it. As stated above, and contrary to a rather wide misunderstanding by Catholics, perspicuity does not mean that everything in the Bible is absolutely clear but that the main message is clear. That is, all doctrines essential for salvation and living according to the will of God are sufficiently clear.

Indeed, to assume that oral traditions of the apostles, not written in the Bible, are necessary to interpret what is written in the Bible under inspiration is to argue that the uninspired is more clear than the inspired. But it is utterly presumptuous to assert that what fallible human beings pronounce is clearer than what the infallible Word of God declares. Further, it is unreasonable to insist that words of the apostles that were not written down are more clear than the ones they did write. We all know from experience that this is not so.

Tradition and Scripture Are Not Inseparable

Kreeftʹs claim that Scripture and apostolic tradition are inseparable is unconvincing. Even his illustration of the horse (Scripture) and the rider (tradition) would suggest that Scripture and apostolic tradition are separable. Further, even if it is granted that tradition is necessary, the Catholic inference that it has to be infallible tradition — indeed, the infallible tradition of the church of Rome — is unfounded. Protestants, who believe in sola Scriptura, accept genuine tradition; they simply do not believe it is infallible. Finally, Kreeftʹs argument wrongly assumes that the Bible was produced by the Roman Catholic church. As we will see in the next point, this is not the case.

The Principle of Causality Is Not Violated

Kreeftʹs argument that sola Scriptura violates the principle of causality is invalid for one fundamental reason: it is based on a false assumption. He wrongly assumes, unwittingly in contrast to what Vatican II and even Vatican I say about the canon,13 that the church determined the canon. In fact, God determined the canon by inspiring these books and no others. The church merely discovered which books God had determined (inspired) to be in the canon. This being the case, Kreeftʹs argument that the cause must be equal to its effect (or greater) fails.

Rejection of Tradition Does Not Necessitate Scandal

Kreeftʹs claim that the rejection of the Roman Catholic view on infallible tradition leads to the scandal of denominationalism does not follow for many reasons. First, this wrongly implies that all denominationalism is scandalous. Not necessarily so, as long as the denominations do not deny the essential doctrines of the Christian church and true spiritual unity with other believers in contrast to mere external organizational uniformity. Nor can one argue successfully that unbelievers are unable to see spiritual unity. For Jesus declared: ʺThis is how all [men] will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one anotherʺ (John 13:35).

Second, as orthodox Catholics know well, the scandal of liberalism is as great inside the Catholic church as it is outside of it. When Catholic apologists claim there is significantly more doctrinal agreement among Catholics than Protestants, they must mean between orthodox Catholics and all Protestants (orthodox and unorthodox) — which, of course, is not a fair comparison.

Only when one chooses to compare things like the mode and candidate for baptism, church government, views on the Eucharist, and other less essential doctrines are there greater differences among orthodox Protestants. When, however, we compare the differences with orthodox Catholics and orthodox Protestants or with all Catholics and all Protestants on the more essential doctrines, there is no significant edge for Catholicism. This fact negates the value of the alleged infallible teaching Magisterium of the Roman Catholic church. In point of fact, Protestants seem to do about as well as Catholics on unanimity of essential doctrines with only an infallible Bible and no infallible interpreters of it!

Third, orthodox Protestant ʺdenominations,ʺ though there be many, have not historically differed much more significantly than have the various ʺordersʺ of the Roman Catholic church. Orthodox Protestantsʹ differences are largely over secondary issues, not primary (fundamental) doctrines. So this Catholic argument against Protestantism is self‐condemning.

Fourth, as J. I. Packer noted, ʺthe real deep divisions have been caused not by those who maintained sola Scriptura, but by those, Roman Catholic and Protestant alike, who reject it.ʺ Further, ʺwhen adherents of sola Scriptura have split from each other the cause has been sin rather than Protestant biblicism….ʺ14 Certainly this is often the case. A bad hermeneutic (method of interpreting Scripture) is more crucial to deviation from orthodoxy than is the rejection of an infallible tradition in the Roman Catholic church.

First Century Christians Had Scripture and Living Apostles

Kreeftʹs argument that the first generation of Christians did not have the New Testament, only the church to teach them, overlooks several basic facts. First, the essential Bible of the early first century Christians was the Old

Testament, as the New Testament itself declares (cf. 2 Tim. 3:15‐17; Rom. 15:4; 1 Cor. 10:6). Second, early New Testament believers did not need further revelation through the apostles in written form for one very simple reason: they still had the living apostles to teach them. As soon as the apostles died, however, it became imperative for the written record of their infallible teaching to be available. And it was — in the apostolic writings known as the New Testament. Third, Kreeftʹs argument wrongly assumes that there was apostolic succession (see Part Four, next issue). The only infallible authority that succeeded the apostles was their infallible apostolic writings, that is, the New Testament.

PROTESTANT ARGUMENTS AGAINST INFALLIBLE TRADITION

There are many reasons Protestants reject the Roman Catholic claim that there is an extrabiblical apostolic tradition of equal reliability and authenticity to Scripture. The following are some of the more significant ones.

Oral Traditions Are Unreliable

In point of fact, oral traditions are notoriously unreliable. They are the stuff of which legends and myths are made. What is written is more easily preserved in its original form. Dutch theologian Abraham Kuyper notes four advantages of a written revelation: (1) It has durability whereby errors of memory or accidental corruptions, deliberate or not, are minimized; (2) It can be universally disseminated through translation and reproduction; (3) It has the attribute of fixedness and purity; (4) It is given a finality and normativeness which other forms of communication cannot attain.15

By contrast, what is not written is more easily polluted. We find an example of this in the New Testament. There was an unwritten ʺapostolic traditionʺ (i.e., one coming from the apostles) based on a misunderstanding of what Jesus said. They wrongly assumed that Jesus affirmed that the apostle John would not die. John, however, debunked this false tradition in his authoritative written record (John 21:22‐23).

Common sense and historical experience inform us that the generation alive when an alleged revelation was given is in a much better position to know if it is a true revelation than are succeeding generations, especially those hundreds of years later. Many traditions proclaimed to be divine revelation by the Roman Catholic Magisterium were done so centuries, even a millennia or so, after they were allegedly given by God. And in the case of some of these, there is no solid evidence that the tradition was believed by any significant number of orthodox Christians until centuries after they occurred. But those living at such a late date are in a much inferior position than contemporaries, such as those who wrote the New Testament, to know what was truly a revelation from God.

There Are Contradictory Traditions

It is acknowledged by all, even by Catholic scholars, that there are contradictory Christian traditions. In fact, the great medieval theologian Peter Abelard noted hundreds of differences. For example, some fathers (e.g., Augustine) supported the Old Testament Apocrypha while others (e.g., Jerome) opposed it. Some great teachers (e.g., Aquinas) opposed the Immaculate Conception of Mary while others (e.g., Scotus) favored it. Indeed, some fathers opposed sola Scriptura, but others favored it.

Now this very fact makes it impossible to trust tradition in any authoritative sense. For the question always arises: which of the contradictory traditions (teachings) should be accepted? To say, ʺThe one pronounced authoritative by the churchʺ begs the question, since the infallibility of tradition is a necessary link in the argument for the very doctrine of the infallible authority of the church. Thus this infallibility should be provable without appealing to the Magisterium. The fact is that there are so many contradictory traditions that tradition, as such, is rendered unreliable as an authoritative source of dogma.

Nor does it suffice to argue that while particular fathers cannot be trusted, nonetheless, the ʺunanimous consentʺ of the fathers can be. For there is no unanimous consent of the fathers on many doctrines ʺinfalliblyʺ proclaimed by the Catholic church (see below). In some cases there is not even a majority consent. Thus to appeal to the teaching Magisterium of the Catholic church to settle the issue begs the question.

The Catholic response to this is that just as the bride recognizes the voice of her husband in a crowd, even so the church recognizes the voice of her Husband in deciding which tradition is authentic. The analogy, however, is faulty. First, it assumes (without proof) that there is some divinely appointed postapostolic way to decide — extrabiblically — which traditions were from God.

Second, historical evidence such as that which supports the reliability of the New Testament is not to be found for the religious tradition used by Roman Catholics. There is, for example, no good evidence to support the existence of first century eyewitnesses (confirmed by miracles) who affirm the traditions pronounced infallible by the Roman Catholic church. Indeed, many Catholic doctrines are based on traditions that only emerge several centuries later and are disputed by both other traditions and the Bible (e.g., the Bodily Assumption of Mary).

Finally, the whole argument reduces to a subjective mystical experience that is given plausibility only because the analogy is false. Neither the Catholic church as such, nor any of its leaders, has experienced down through the centuries anything like a continual hearing of Godʹs actual voice, so that it can recognize it again whenever He speaks. The truth is that the alleged recognition of her Husbandʹs voice is nothing more than subjective faith in the teaching Magisterium of the Roman Catholic church.

Catholic Use of Tradition Is Not Consistent

Not only are there contradictory traditions, but the Roman Catholic church is arbitrary and inconsistent in its choice of which tradition to pronounce infallible. This is evident in a number of areas. First, the Council of Trent chose to follow the weaker tradition in pronouncing the apocryphal books inspired. The earliest and best authorities, including the translator of the Roman Catholic Latin Vulgate Bible, St. Jerome, opposed the Apocrypha.

Second, support from tradition for the dogma of the Bodily Assumption of Mary is late and weak. Yet despite the lack of any real evidence from Scripture or any substantial evidence from the teachings of early church fathers, Rome chose to pronounce this an infallible truth of the Catholic faith. In short, Roman Catholic dogmas at times do not grow out of rationally weighing the evidence of tradition but rather out of arbitrarily choosing which of the many conflicting traditions they wish to pronounce infallible. Thus, the ʺunanimous consent of the fathersʺ to which Trent commanded allegiance is a fiction.

Third, apostolic tradition is nebulous. As has often been pointed out, ʺNever has the Roman Catholic Church given a complete and exhaustive list of the contents of extrabiblical apostolic tradition. It has not dared to do so because this oral tradition is such a nebulous entity.ʺ16 That is to say, even if all extrabiblical revelation definitely exists somewhere in some tradition (as Catholics claim), which ones these are has nowhere been declared.

Finally, if the method by which they choose which traditions to canonize were followed in the practice of textual criticism of the Bible, one could never arrive at a sound reconstruction of the original manuscripts. For textual criticism involves weighing the evidence as to what the original actually said, not reading back into it what subsequent generations would like it to have said. Indeed, even most contemporary Catholic biblical scholars do not follow such an arbitrary procedure when determining the translation of the original text of Scripture (as in The New American Bible).

In conclusion, the question of authority is crucial to the differences between Catholics and Protestants. One of these is whether the Bible alone has infallible authority. We have examined carefully the best Catholic arguments in favor of an additional authority to Scripture, infallible tradition, and found them all wanting. Further, we have advanced many reasons for accepting the Bible alone as the sufficient authority for all matters of faith and morals. This is supported by Scripture and sound reason. In Part Four we will go further in our examination of Catholic authority by evaluating the Catholic dogma of the infallibility of the Pope.

Dr. Norman L. Geisler is Dean of Southern Evangelical Seminary in Charlotte, NC. He is author or co‐author of over 40 books and has his Ph.D. in philosophy from Loyola University, a Roman Catholic school in Chicago.

Ralph E. MacKenzie has dialogued with Roman Catholics for 40 years. He graduated from Bethel Theological Seminary West, earning a Master of Arts in Theological Studies (M.A.T.S.), with a concentration in church history.

NOTES

1 See Kenneth R. Samples, ʺWhat Think Ye of Rome?ʺ (Parts One and Two), Christian Research Journal, Winter (pp. 3242) and Spring (pp. 32‐42) 1993.

2 Some Reformed theologians wish to point out that the material principle is really ʺin Christ aloneʺ and faith alone is the means of access.

3 Henry Denzinger, The Sources of Catholic Dogma (London: B. Herder Book Co., 1957) [section] 783, 244. From the Council of Trent, Session 4 (April 8, 1546).

4 Denzinger, ʺSystematic Index,ʺ 11.

5 [sections] 995, 303.

6 See Patrick Madrid, ʺGoing Beyond,ʺ This Rock, August 1992, 22‐23.

7 Peter Kreeft, Fundamentals of the Faith (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), 274‐75.

8 Ibid

9 Ibid

10 Ibid

11 There is some debate even among Protestant scholars as to whether Paul is referring here to his own previous statements or to Scripture as a whole. Since the phrase used here is reserved only for Sacred Scripture (cf. 2 Tim. 3:15‐16) the latter seems to be the case.

12 D. N. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrine (New York: Harper & Row, 1960), 42‐43.

13 See Austin Flannery, gen. ed., Vatican Council II, 1, rev. ed. (Boston: St. Paul Books & Media, 1992), Dei Verbum, 750‐65 and Denzinger, [section] 1787, 444.

14 I. Packer, ʺSola Scriptura: Crucial to Evangelicalism,ʺ in The Foundations of Biblical Authority, ed. James Boice

(Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1978), 103.

15 See Bruce Milne, Know the Truth (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1982), 28.

16 Bernard Ramm, The Pattern of Authority (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1959), 68.

What Think Ye of Rome? Part Four: The Catholic-Protestant Debate on Papal Infallibility

by Norman L. Geisler and Ralph E. MacKenzie

SUMMARY

Papal infallibility was formalized at the First Vatican Council, A.D. 1870. It is required belief for Roman Catholics but is rejected by evangelicals. On examination, the major biblical texts used to defend this dogma do not support the Catholic position. Further, there are serious theological and historical problems with the doctrine of papal infallibility. Infallibility stands as an irrevocable roadblock to any ecclesiastical union between Catholics and Protestants.

According to Roman Catholic dogma, the teaching magisterium of the church of Rome is infallible when officially defining faith and morals for believers. One manifestation of this doctrine is popularly known as “papal infallibility.” It was pronounced a dogma in A.D. 1870 at the First Vatican Council. Since this is a major bone of contention between Catholics and Protestants, it calls for attention here.

THE DOCTRINE EXPLAINED

Roman Catholic authorities define infallibility as “immunity from error, i.e., protection against either passive or active deception. Persons or agencies are infallible to the extent that they can neither deceive nor be deceived.”[1]

Regarding the authority of the pope, Vatican I pronounced that all the faithful of Christ must believe “that the Apostolic See and the Roman Pontiff hold primacy over the whole world, and that the Pontiff of Rome himself is the successor of the blessed Peter, the chief of the apostles, and is the true [vicar] of Christ and head of the whole Church and faith, and teacher of all Christians; and that to him was handed down in blessed Peter, by our Lord Jesus Christ, full power to feed, rule, and guide the universal Church, just as is also contained in the records of the ecumenical Councils and in the sacred canons.”[2]

Furthermore, the Council went on to speak of “The Infallible ‘Magisterium’ [teaching authority] of the Roman Pontiff,” declaring that when he speaks ex cathedra, that is, when carrying out the duty of the pastor and teacher of all Christians in accord with his supreme apostolic authority he explains a doctrine of faith or morals to be held by the Universal Church, through the divine assistance promised him in blessed Peter, operates with that infallibility with which the divine Redeemer wished that His church be instructed in defining doctrine on faith and morals; and so such definitions of the Roman Pontiff from himself, but not from the consensus of the Church, are unalterable. [emphases added][3]

Then follows the traditional condemnation on any who reject papal infallibility: “But if anyone presumes to contradict this definition of Ours, which may God forbid: let him be anathema” [i.e., excommunicated].[4]

Qualifications

Roman Catholic scholars have expounded significant qualifications on the doctrine. First, they acknowledge that the pope is not infallible in everything he teaches but only when he speaks ex cathedra, as the official interpreter of faith and morals. Avery Dulles, an authority on Catholic dogma, states for a pronouncement to be ex cathedra it must be:

(1) in fulfillment of his office as supreme pastor and teacher of all Christians;

(2) in virtue of his supreme apostolic authority, i.e., as successor of Peter;

(3) determining a doctrine of faith and morals, i.e., a doctrine expressing divine revelation;

(4) imposing a doctrine to be held definitively by all.[5]

Dulles notes that “Vatican I firmly rejected one condition…as necessary for infallibility, namely, the consent of the whole church.”[6]

Second, the pope is not infallible when pronouncing on matters that do not pertain to “faith and morals.” On these matters he may be as fallible as anyone else.

Third, although the pope is infallible, he is not absolutely so. As Dulles observes, “absolute infallibility (in all respects, without dependence on another) is proper to God….All other infallibility is derivative and limited in scope.”[7]

Fourth, infallibility entails irrevocability. A pope cannot, for example, declare previous infallible pronouncements of the church void.

Finally, in contrast to Vatican I, many (usually liberal or progressive) Catholic theologians believe that the pope is not infallible independent of the bishops but only as he speaks in one voice with and for them in collegiality. As Dulles noted, infallibility “is often attributed to the bishops as a group, to ecumenical councils, and to popes.”[8] Conservatives argue that Vatican I condemned this view.[9]

A PROTESTANT RESPONSE

Not only Protestants but the rest of Christendom — Anglicans and Eastern Orthodox included — reject the doctrine of papal infallibility.[10] Protestants accept the infallibility of Scripture but deny that any human being or institution is the infallible interpreter of Scripture. Harold O. J. Brown writes: “In every age there have been those who considered the claims of a single bishop to supreme authority to be a sure identification of the corruption of the church, and perhaps even the work of the Antichrist. Pope Gregory I (A.D. 590-604) indignantly reproached Patriarch John the Faster of Constantinople for calling himself the universal bishop; Gregory did so to defend the rights of all the bishops, himself included, and not because he wanted the title for himself.”[11]

Biblical Problems

There are several texts Catholics use to defend the infallibility of the bishop of Rome. We will focus here on the three most important of these.

Matthew 16:18ff. Roman Catholics use the statement of Jesus to Peter in Matthew 16:18ff. that “upon this rock I will build my church…” to support papal infallibility. They argue that the truth of the church could only be secure if the one on whom it rested (Peter) were infallible. Properly understood, however, there are several reasons this passage falls far short of support for the dogma of papal infallibility.

First, many Protestants insist that Christ was not referring to Peter when he spoke of “this rock” being the foundation of the church.[12] They note that: (1) Whenever Peter is referred to in this passage it is in the second person (“you”), but “this rock” is in the third person. (2) “Peter” (petros) is a masculine singular term and “rock” (petra) is feminine singular. Hence, they do not have the same referent. And even if Jesus did speak these words in Aramaic (which does not distinguish genders), the inspired Greek original does make such distinctions. (3) What is more, the same authority Jesus gave to Peter (Matt. 16:18) is given later to all the apostles (Matt. 18:18). (4) Great authorities, some Catholic, can be cited in agreement with this interpretation, including John Chrysostom and St. Augustine. The latter wrote: “On this rock, therefore, He said, which thou hast confessed. I will build my Church. For the Rock (petra) is Christ; and on this foundation was Peter himself built.”[13]

Second, even if Peter is the rock referred to by Christ, as even some non-Catholic scholars believe, he was not the only rock in the foundation of the church. Jesus gave all the apostles the same power (“keys”) to “bind” and “loose” that he gave to Peter (cf. Matt. 18:18). These were common rabbinic phrases used of “forbidding” and “allowing.” These “keys” were not some mysterious power given to Peter alone but the power granted by Christ to His church by which, when they proclaim the Gospel, they can proclaim God’s forgiveness of sin to all who believe. As John Calvin noted, “Since heaven is opened to us by the doctrine of the gospel, the word ‘keys’ affords an appropriate metaphor. Now men are bound and loosed in no other way than when faith reconciles some to God, while their own unbelief constrains others the more.”[14]

Further, Scripture affirms that the church is “built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the capstone” (Eph. 2:20). Two things are clear from this: first, all the apostles, not just Peter, are the foundation of the church; second, the only one who was given a place of uniqueness or prominence was Christ, the capstone. Indeed, Peter himself referred to Christ as “the cornerstone” of the church (1 Pet. 2:7) and the rest of believers as “living stones” (v. 4) in the superstructure of the church. There is no indication that Peter was given a special place of prominence in the foundation of the church above the rest of the apostles and below Christ. He is one “stone” along with the other eleven apostles (Eph. 2:20).

Third, Peter’s role in the New Testament falls far short of the Catholic claim that he was given unique authority among the apostles for numerous reasons.[15]

(1) While Peter did preach the initial sermon on the day of Pentecost, his role in the rest of Acts is scarcely that of the chief apostle but at best one of the “most eminent apostles” (plural, 2 Cor. 21:11, NKJV).

(2) No one reading Galatians carefully can come away with the impression that any apostle, including Peter, is superior to the apostle Paul. For he claimed to get his revelation independent of the other apostles (Gal. 1:12; 2:2) and to be on the same level as Peter (2:8), and he even used his revelation to rebuke Peter (2:11-14).

(3) Indeed, if Peter was the God-ordained superior apostle, it is strange that more attention is given to the ministry of the apostle Paul than to that of Peter in the Book of Acts. Peter is the central figure among many in chapters 1-12, but Paul is the dominant focus of chapters 13-28.[16]

(4) Furthermore, though Peter addressed the first council (in Acts 15), he exercised no primacy over the other apostles. Significantly, the decision came from “the apostles and presbyters, in agreement with the whole church” (15:22; cf. v. 23). Many scholars believe that James, not Peter, exercised leadership over the council, since he brought the final words and spoke decisively concerning what action should be taken (vv. 13-21).[17]

(5) In any event, by Peter’s own admission he was not the pastor of the church but only a “fellow presbyter [elder]” (1 Pet. 5:1-2, emphasis added). And while he did claim to be “an apostle” (1 Pet. 1:1) he nowhere claimed to be “the apostle” or the chief of apostles. He certainly was a leading apostle, but even then he was only one of the “pillars” (plural) of the church along with James and John, not the pillar (see Gal. 2:9).

This is not to deny that Peter had a significant role in the early church; he did. He even seems to have been the initial leader of the apostolic band. As already noted, along with James and John he was one of the “pillars” of the early church (Gal. 2:9). For it was he that preached the great sermon at Pentecost when the gift of the Holy Spirit was given, welcoming many Jews into the Christian fold. It was Peter also who spoke when the Spirit of God fell on the Gentiles in Acts 10. From this point on, however, Peter fades into the background and Paul is the dominant apostle, carrying the gospel to the ends of the earth (Acts 13-28), writing some one-half of the New Testament (as compared to Peter’s two epistles), and even rebuking Peter for his hypocrisy (Gal. 2:11-14). In short, there is no evidence in Matthew 16 or any other text for the Roman Catholic dogma of the superiority, to say nothing of the infallibility, of Peter. He did, of course, write two infallible books (1 and 2 Peter), as did other apostles.

John 21:15ff. In John 21:15ff. Jesus says to Peter, “Feed my lambs” and “Tend my sheep” and “Feed my sheep” (vv. 15, 16, 17). Roman Catholic scholars believe this shows that Christ made Peter the supreme pastor of the church. This means he must protect the church from error, they say, and to do so he must necessarily be infallible. But this is a serious overclaim for the passage.

First, whether this text is taken of Peter alone or of all the disciples, there is absolutely no reference to any infallible authority. Jesus’ concern here is simply a matter of pastoral care. Feeding is a God-given pastoral function that even nonapostles have in the New Testament (cf. Acts 20:28; Eph. 4:11-12; 1 Pet. 5:1-2). One does not have to be an infallible shepherd in order to feed one’s flock properly.

Second, if Peter had infallibility (the ability not to mislead), then why did he mislead believers and have to be rebuked by the apostle Paul for so doing? The infallible Scriptures, accepted by Roman Catholics, declared of Peter on one occasion, “He clearly was wrong” and “stood condemned.”[18] Peter and others “acted hypocritically…with the result that even Barnabas was carried away by their hypocrisy.” And hypocrisy here is defined by the Catholic Bible (NAB) as “pretense, play-acting; moral insincerity.” It seems difficult to exonerate Peter from the charge that he led believers astray. And this failing is hard to reconcile with the Roman Catholic claim that, as the infallible pastor of the church, he could never do so! The Catholic response — that Peter was not infallible in his actions, only his ex cathedra words — rings hollow when we remember that “actions speak louder than words.” By his actions he was teaching other believers a false doctrine concerning the need for Jewish believers to separate themselves from Gentile believers. The fact is that Peter cannot be both an infallible guide for faith and morals and also at the same time mislead other believers on the important matter of faith and morals of which Galatians speaks.

Third, in view of the New Testament terminology used of Peter it is clear that he would never have accepted the titles used of the Roman Catholic pope today: “Holy Father” (cf. Matt. 23:9), “Supreme Pontiff,” or “Vicar of Christ.” The only vicar (representative) of Christ on earth today is the blessed Holy Spirit (John 14:16, 26). As noted earlier, Peter referred to himself in much more humble terms as “an apostle,” not the apostle (1 Pet. 1:1, emphasis added) and “fellow-presbyter [elder]” (1 Pet. 5:1, emphasis added), not the supreme bishop, the pope, or the Holy Father.

John 11:49-52. In John 11:49-52 Caiaphas, the High Priest, in his official capacity as High Priest, made an unwitting prophecy about Christ dying for the nation of Israel so that they would not perish. Some Catholics maintain that in the Old Testament the High Priest had an official revelatory function connected with his office, and therefore we should expect an equivalent (namely, the pope) in the New Testament. However, this argument is seriously flawed. First, this is merely an argument from analogy and is not based on any New Testament declaration that it is so. Second, the New Testament affirmations made about the Old Testament priesthood reject that analogy, for they say explicitly that the Old Testament priesthood has been abolished. The writer to the Hebrews declared that “there is a change of priesthood” from that of Aaron (Heb. 7:12). The Aaronic priesthood has been fulfilled in Christ who is a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek (Heb. 7:15-17). Third, even Catholics acknowledge that there is no new revelation after the time of the New Testament function. So no one (popes included) after the first century can have a revelatory function in the proper sense of giving new revelations. Finally, there is a New Testament revelatory function like that of the Old, but it is in the New Testament “apostles and prophets” (cf. Eph. 2:20; 3:5), which revelation ceased when they died. To assume a revelatory (or even infallible defining) function was passed on after them and is resident in the bishop of Rome is to beg the question.

In addition to a total lack of support from the Scriptures, there are many other arguments against papal infallibility. We will divide them into theological and historical arguments.

Theological Problems

There are serious theological problems with papal infallibility. One is the question of heresy being taught by an infallible pope.

The Problem of Heretical Popes. Pope Honorius I (A.D. 625-638) was condemned by the Sixth General Council for teaching the monothelite heresy (that there was only one will in Christ[19]). Even Roman Catholic expert, Ludwig Ott, admits that “Pope Leo II (682-683) confirmed his anathematization…”[20] This being the case, we are left with the incredible situation of an infallible pope teaching a fallible, indeed heretical, doctrine. If the papal teaching office is infallible — if it cannot mislead on doctrine and ethics — then how could a papal teaching be heretical? This is misleading in doctrine in the most serious manner.

To claim that the pope was not infallible on this occasion is only to further undermine the doctrine of infallibility. How can one know just when his doctrinal pronouncements are infallible and when they are not? There is no infallible list of which are the infallible pronouncements and which are not.[21] But without such a list, how can the Roman Catholic church provide infallible guidance on doctrine and morals? If the pope can be fallible on one doctrine, why cannot he be fallible on another?

Further, Ott’s comment that Pope Leo did not condemn Pope Honorius with heresy but with “negligence in the suppression of error” is ineffective as a defense.[22] First, it still raises serious questions as to how Pope Honorius could be an infallible guide in faith and morals, since he taught heresy. And the Catholic response that he was not speaking ex cathedra when he taught this heresy is convenient but inadequate. Indeed, invoking such a distinction only tends to undermine faith in the far more numerous occasions when the pope is speaking with authority but not with infallibility.

Second, it does not explain the fact that the Sixth General Council did condemn Honorius as a heretic, as even Ott admits.[23] Was this infallible Council in error?

Finally, by disclaiming the infallibility of the pope in this and like situations, the number of occasions on which infallible pronouncements were made is relatively rare. For example, the pope has officially spoken ex cathedra only one time this whole century (on the Bodily Assumption of Mary)! If infallibility is exercised only this rarely then its value for all practical purposes on almost all occasions is nill. This being the case, since the pope is only speaking with fallible authority on the vast majority of occasions, the Catholic is bound to accept his authority on faith and morals when he may (and sometimes has been) wrong. In short, the alleged infallible guidance the papacy is supposed to provide is negligible at best. Indeed, on the overwhelming number of occasions there is no infallible guidance at all.

The Problem of Revelational Insufficiency. One of the chief reasons given by Catholic authorities as to the need for an infallible teaching magisterium is that we need infallible guidance to understand God’s infallible revelation. Otherwise it will be misinterpreted as with the many Protestant sects.

To this the Protestant must respond, How is an infallible interpretation any better than the infallible revelation? Divine revelation is a disclosure or unveiling by God. But to claim, as Catholics do, that God’s infallible unveiling in the Bible needs further infallible unveiling by God is to say that it was not unveiled properly to begin with.

To be sure, there is a difference between objective disclosure (revelation) and subjective discovery (understanding). But the central problem in this regard is not in the perception of God’s truth. Even His special revelation is “evident” and “able to be understood” (Rom. 1:19-20). Our most significant problem with regard to the truth of God’s revelation is reception. Paul declared that “the natural person does not accept [Gk: dekomai, welcome, receive] what pertains to the Spirit of God…” (1 Cor. 2:14). He cannot “know” (ginosko: know by experience) them because he does not receive them into his life, even though he understands them in his mind. So even though there is a difference between objective disclosure and subjective understanding, humans are “without excuse” for failing to understand the objective revelation of God, whether in nature or in Scripture (Rom. 1:20).

In this regard it is interesting that Catholic theology itself maintains that unbelievers should and can understand the truth of natural law apart from the teaching magisterium. Why then should they need an infallible teaching magisterium in order to properly understand the more explicit divine law?

It seems singularly inconsistent for Catholic scholars to claim they need another mind to interpret Scripture correctly for them when the mind God gave them is sufficient to interpret everything else, including some things much more difficult than Scripture. Many Catholic scholars, for example, are experts in interpreting classical literature, involving both the moral and religious meaning of those texts. Yet these same educated minds are said to be inadequate to obtain a reliable religious and moral interpretation of the texts of their own Scriptures.

Furthermore, it does not take an expert to interpret the crucial teachings of the Bible. The New Testament was written in the vernacular of the times, the trade-language of the first century, known as koine Greek. It was a book written in the common, everyday language for the common, everyday person. Likewise, the vast majority of English translations of the Bible are also written in plain English, including Catholic versions. The essential truths of the Bible can be understood by any literate person. In fact, it is an insult to the intelligence of the common people to suggest that they can read and understand the daily news for themselves but need an infallible teaching magisterium in order to understand God’s Good News for them in the New Testament.

The Problem of Indecisiveness of the Teaching Magisterium. There is another problem with the Catholic argument for an infallible teaching magisterium: if an infallible teaching magisterium is needed to overcome the conflicting interpretations of Scripture, why is it that even these “infallibly” decisive declarations are also subject to conflicting interpretations? There are many hotly disputed differences among Catholic scholars on just what ex cathedra statements mean, including those on Scripture, tradition, Mary, and justification. Even though there may be future clarifications on some of these, the problem remains for two reasons. First, it shows the indecisive nature of supposedly infallible pronouncements. Second, judging by past experience, even these future declarations will not settle all matters completely. Pronouncements on the inerrancy of Scripture are a case in point. Despite “infallible” statements, there is strong disagreement among Catholics on whether the Bible is really infallible in all matters or only on matters of salvation.

Historical Problems

In addition to biblical and theological problems, there are serious historical problems with the Catholic claim for infallibility. Two are of special note here.

The Problem of the Antipopes. Haunting the history of Roman Catholicism is the scandalous specter of having more than one infallible pope at the same time — a pope and an antipope. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church says “there have been about thirty-five antipopes in the history of the Church.”[24] How can there be two infallible and opposing popes at the same time? Which is the true pope? Since there is no infallible list of popes or even an infallible way to determine who is the infallible pope, the system has a serious logical problem. Further, this difficulty has had several actual historical manifestations which bring into focus the whole question of an infallible pope.[25]

Catholic apologists claim that there were not really two popes, since only one can be infallible. However, since the faithful have no way to know for sure which one is the pope, which one should they look to for guidance? Each pope can excommunicate the other (and sometimes have). This being the case, claiming that only one is the real pope is at best only a theoretical solution. It does not solve the practical problem of which pope should be followed.

The Problem of Galileo. Perhaps one of the greatest embarrassments to the “infallible” church is its fallible judgment about Galileo Galilei (A.D. 1564-1642), generally known as Galileo. In opposition to Galileo and the Copernican solar-centric theory he adopted, the Catholic church sided with the scientifically outdated Ptolemaic geocentric universe.

In A.D. 1616, the Copernican theory was condemned at Rome.[26] Aristotelian scientists, the Jesuits, the Dominicans, and three popes (Paul V, Gregory XV, and Urban VIII), played key roles in the controversy. Galileo was summoned by the Inquisition in 1632, tried, and on June 21, 1633, pronounced “vehemently suspected of heresy.” Eventually Pope Urban VIII allowed Galileo to return to his home in Florence, where he remained under house arrest until his death in 1642.

After the church had suffered many centuries of embarrassment for its condemnation of Galileo, on November 10, 1979, Pope John Paul II spoke to the Pontifical Academy of Science. In the address titled, “Faith, Science and the Galileo Case,” the pope called for a reexamination of the whole episode.[27] On May 9, 1983, while addressing the subject of the church and science, John Paul II conceded that “Galileo had ‘suffered from departments of the church.'”[28] This, of course, is not a clear retraction of the condemnation, nor does it solve the problem of how an infallible pronouncement of the Catholic church could be in error.

Roman Catholic responses to the Galileo episode leave something to be desired. One Catholic authority claims that while both Paul V and Urban VIII were committed anti-Copernicans, their pronouncements were not ex cathedra. The decree of A.D. 1616 “was issued by the Congregation of the Index, which can raise no difficulty in regard of infallibility, this tribunal being absolutely incompetent to make a dogmatic decree.”[29] As to the second trial in 1633, which also resulted in a condemnation of Galileo, this sentence is said to be of lesser importance because it “did not receive the Pope’s signature.”[30] Another Catholic authority states that although the theologians’ treatment of Galileo was inappropriate, “the condemnation was the act of a Roman Congregation and in no way involved infallible teaching authority.”[31] Still another source observes, “The condemnation of Galileo by the Inquisition had nothing to do with the question of papal infallibility, since no question of faith or morals was papally condemned ex cathedra.”[32] And yet another Catholic apologist suggests that, although the decision was a “regrettable” case of “imprudence,” there was no error made by the pope, since Galileo was not really condemned of heresy but only strongly suspected of it.

None of these ingenious solutions is very convincing, having all the earmarks of after-the-fact tinkering with the pronouncements that resulted from this episode. Galileo and his opponents would be nonplussed to discover that the serious charges leveled against him were not “ex cathedra” in force. And in view of the strong nature of both the condemnation and the punishment, he would certainly be surprised to hear Catholic apologists claim that he was not really being condemned for false teaching but only that “his ‘proof’ did not impress even astronomers of that day — nor would they impress astronomers today”![33]

At any rate, the pope’s condemnation of Galileo only leads to undermine the alleged infallibility of the Catholic church. Of course, Catholic apologists can always resort to their apologetic warehouse — the claim that the pope was not really speaking infallibly on that occasion. As we have already observed, however, constant appeal to this nonverifiable distinction only tends to undermine the very infallibility it purports to defend.

AN IMPASSABLE ROADBLOCK

Despite the common creedal and doctrinal heritage of Catholics and Protestants, there are some serious differences.[34] None of these is more basic than the question of authority. Catholics affirm de fide, as an unchangeable part of their faith, the infallible teaching authority of the Roman church as manifested in the present bishop of Rome (the pope). But what Catholics affirm “infallibly” Protestants deny emphatically. This is an impassable roadblock to any ecclesiastical unity between Catholicism and orthodox Protestantism. No talk about “first among equals” or “collegiality” will solve the problem. For the very concept of an infallible teaching magisterium, however composed, is contrary to the basic Protestant principle of sola Scriptura, the Bible alone (see Part Three). Here we must agree to disagree. For while both sides believe the Bible is infallible, Protestants deny that the church or the pope has an infallible interpretation of it.

About the Author

Dr. Geisler is Dean of Southern Evangelical Seminary, Charlotte, North Carolina .

NOTES

1 Avery Dulles, “Infallibility: The Terminology,” in Teaching Authority and Infallibility in the Church, ed. Paul C. Empie, T. Austin Murphy, and Joseph A. Burgess (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1978), 71.

2 Henry Denzinger, The Sources of Catholic Dogma, trans. Roy J. Deferrari (London: B. Herder Book Co., 1957), no. 1826, 454.

3 Ibid., no. 1839, 457.

4 Ibid., no. 1840.

5 Dulles, 79-80.

6 Ibid.,

7 Ibid., 72.

8 Ibid.

9 They appeal to Denzinger 1839 to support their view.

10 Eastern Orthodoxy is willing to accept the bishop of Rome as “first among equals,” a place of honor coming short of the total superiority Roman Catholics ascribe to the pope.

11 Harold O. J. Brown, The Protest of a Troubled Protestant (New York: Arlington House, 1969), 122.

12 See James R. White, Answers to Catholic Claims (Southbridge, MA: Crowne Publications, 1990), 104-8.

13 Augustine, “On the Gospel of John,” Tractate 12435, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series I (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1983), 7:450, as cited in Ibid., 106.

14 John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1960) 4:6,4, p. 1105.

15 Many of these arguments are found in White, 101-2.

16 One cannot, as some Catholic scholars do, dismiss this dominant focus on St. Paul rather than Peter on the circumstantial fact that Luke wrote more about Paul because he was his travel companion. After all, it was the Holy Spirit who inspired what Luke wrote.

17 See F. F. Bruce, Peter, Stephen, James and John (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1979), 86ff.

18 This is the literal rendering given in the Roman Catholic New American Bible of Galatians 2:11.

19 See John Jefferson Davis, Foundations of Evangelical Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1994). Also see Ott, 238.

20 Ott, 150.

21 Catholic apologists claim there are objective tests, such as: Was the pope speaking (1) to all believers, (2) on faith and morals, and (3) in his official capacity as pope (see Ott, 207). But these are not definitive as to which pronouncements are infallible for several reasons. First, there is no infallible statement on just what these criteria are. Second, there is not even universal agreement on what these criteria are. Third, there is no universal agreement on how to apply these or any criteria to all cases.

22 Ott, 150.

23 Ibid.

24 F. L. Cross, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), 66. See also, A. Mercati, “The New List of the Popes,” in Medieval Studies, ix (1947), 71-80.

25 See Jarislov Pelikan, The Riddle of Roman Catholicism (New York: Abingdon Press, 1960), 40.

26 New Catholic Encyclopedia, 15 vols., prepared by an editorial staff at the Catholic University of America, Washington, DC (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1967), vol. 6, 252.

27 Brown, 177, n. 4.

28 Ibid. See also “Discourse to Scientists on the 350th Anniversary of the Publication of Galileo’s ‘Dialoghi,'” in J. Neuner, S.J. and J. Dupuis, S.J., eds., The Christian Faith: Doctrinal Documents of the Catholic Church (New York: Alba House, 1990), 68.

29 Charles G. Herbermann, et al., The Catholic Encyclopedia, 15 vols. and index (New York: Robert Appleton Co., 1909), vol. 6, 345.

30 Ibid., 346.

31 New Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 6, 254.

32 “Galileo Galilei,” in John J. Delaney and James E. Tobin, Dictionary of Catholic Biography (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1961), 456.

33 See William G. Most, Catholic Apologetics Today: Answers to Modern Critics (Rockford, IL: Tan Books and Publishers, 1986), 168-69.

34 Interestingly, the problem areas for evangelicals have also been addressed by some well-known Roman Catholic authorities, such as Athanasius, Jerome, and Aquinas. The evangelical case could be made for these writers on a number of issues. For example, Jerome did not accept the Catholic apocryphal (deuterocanonical) books and Aquinas rejected the doctrine of the immaculate conception of Mary.

WHAT THINK YE OF ROME? (Part Five): The Catholic‐Protestant Debate on Justification1

by Norman L. Geisler, and Ralph E. MacKenzie, with Elliot Miller

Summary

The Protestant Reformers recovered the biblical view of forensic justification, that a person is legally declared righteous by God on the basis of faith alone. In so doing, their principle of “salvation by faith alone” gave a more biblical specificity to the common Augustinian view of “salvation by grace alone” held by Catholics and Protestants alike. For although Rome has always held the essential belief in salvation by grace, its view of justification–made dogma by the Council of Trent–obscures the pure grace of God, if not at times negating it in practice.

Roman Catholics and evangelicals share a common core of beliefs about salvation. Both camps are greatly indebted to the same church father (Augustine) for their views on this subject. Despite this common heritage, however, the question of how a person is justified before God has always been a fundamental dividing point between Roman Catholics and Protestants. Recently, the Catholic doctrine of justification has become a divisive issue even among evangelicals, as they seek to determine how far they should go in cooperative relations with Catholics.

In this conclusion to our series on Roman Catholicism, we will examine both the commonalities and differences between Catholic and Protestant soteriology (beliefs about salvation). We will give special attention to the Protestant Reformation doctrine of forensic (legal) justification, and we will provide a Protestant critique of the official Roman Catholic response to that doctrine, as embodied in the decrees of the sixteenth‐century Council of Trent.

JUSTIFICATION IN CHURCH HISTORY

The earliest serious threat to Christian faith was Gnosticism. This was not a clearly defined movement but was made up of various subgroups drawn from Hellenistic as well as Oriental sources. One of the central beliefs of Gnosticism was that salvation is the escape from the physical body (which is evil) achieved by special knowledge (gnosis; hence, Gnosticism). The understanding of the body as evil led some gnostics to stress control of the body and its desires (asceticism). Others were libertines, leaving the body to its own devices and passions.

The early orthodox theologians and apologists devoted much of their effort to combating Gnosticism. In response to the libertines, the early father Tertullian (A.D. 160‐225) focused on the importance of works and righteousness. In so doing he went so far as to say that “the man who performs good works can be said to make God his debtor.”2 This unfortunate affirmation set the stage for centuries to come.

The “works‐righteousness” concept, which seemed to be so ingenious in combating Gnosticism, was popular for the first 350 years of the churchʹs history. However, a controversy that would produce a more precise definition of the theological elements involved was needed. This dispute came on the scene with the system of Pelagius, and the Christian thinker to confront it was Augustine of Hippo.3

Augustine

Augustine (A.D. 354‐430) was an intellectual giant. No one has exercised a greater influence over the development of Western Christian thought than the Bishop of Hippo. In dealing with Augustineʹs doctrine of justification, it is important to note that his thinking on this vital issue underwent significant development. Early on Augustine stressed the role of the human will in matters of salvation, a view he would later modify in his disputations with the British monk, Pelagius.

Pelagiusʹs theological system taught the total freedom of the human will and denied the doctrine of original sin. After reflecting on Pauline insights, the later Augustine came to the following conclusions: First, the eternal decree of Godʹs predestination determines manʹs election. Second, Godʹs offer of grace (salvation) is itself a gift (John 6:44a). Third, the human will is completely unable to initiate or attain salvation. This concept squares quite well with the later Reformed doctrine of total depravity. Fourth, the justified sinner does not merely receive the status of sonship, but becomes one. Fifth, God may regenerate a person without causing that one to finally persevere.4 This is basic Calvinism without the perseverance of all the saints.

It would be incorrect to say that Augustine held to the concept of forensic justification. Nonetheless, he did maintain that salvation is by Godʹs grace. That is, no good works precede or merit initial justification (regeneration). Augustine has been regarded as both the last of the church fathers and the first medieval theologian. He marks the end of one era and the beginning of another.

The Early Medieval Period

The medieval period (the “Middle Ages”) is commonly dated from Augustine (or slightly later) to the 1500s. This period saw the balance of power in the church shift from the East (where Christianity began) to the West or Latin wing of the church.

Pelagianism was officially condemned by the church at the Council of Ephesus (A.D. 431) and again at the Second Council of Orange (A.D. 529), which declared that “if anyone says that the grace of God can be bestowed by human invocation, but that the grace itself does not bring it to pass that it be invoked by us, he contradicts Isias the Prophet….[cf. Isa. 65:l]”5 However, this heresy, along with its more moderate relative semi‐Pelagianism (also condemned at the Council of Orange),6 keeps recurring in church history. It seems that manʹs inclination is toward Pelagianism rather than Augustineʹs Pauline emphasis on the grace of God.

Leo “the Great,” who was the bishop of Rome from A.D. 440‐461, is designated by many non‐Catholic historians as the first “pope” in the modern sense. During his era many Roman Catholic dogmas (which may have existed in germ form earlier) solidified: the supreme authority of the Roman bishop in the church, sacramentalism, sacerdotalism (belief in a priesthood), and the change of emphasis in the Eucharistic Feast from celebration to sacrifice, to name a few. These doctrines influenced medieval soteriology in several ways.

Justification and the Sacraments. During the medieval period baptism and penance were linked with justification. Godʹs righteousness was begun (infused) in baptism and continued (perfected) through penance.

Although this understanding of the nature and purpose of baptism can be found from the earliest of times, the same is not true of the concept of penance. The idea of confession to a priest for the remission of sin existed in the second century but did not become a widespread practice until the early medieval period.