Open Theists and Inerrancy:

Clark Pinnock on the Bible and God

by Norman L. Geisler

Pinnock on the Bible

The Bible is not Completely Inerrant

“This leaves us with the question, Does the New Testament, did Jesus, teach the perfect errorlessness of the Scriptures? No, not in plain terms” (Pinnock, SP, 57).

Although the New Testament does not teach a strict doctrine of inerrancy, it might be said to encourage a trusting attitude, which inerrancy in a more lenient definition does signify. The fact is that inerrancy is a very flexible term in and of itself” (Pinnock, SP, 77).

“Once we recall how complex a hypothesis inerrancy is, it is obvious that the Bible teaches no such thing explicitly. What it claims, as we have seen, is divine inspiration and a general reliability” (Pinnock, SP, 58).

“Why, then, do scholars insist that the Bible does claim total inerrancy? I can only answer for myself, as one who argued in this way a few years ago. I claimed that the Bible taught total inerrancy because I hoped that it did-I wanted it to” (Pinnock, SP, 58).

“For my part, to go beyond the biblical requirements to a strict position of total errorlessness only brings to the forefront the perplexing features of the Bible that no one can completely explain and overshadows those wonderful certainties of salvation in Christ that ought to be front and center” (Pinnock, SP, 59).

The Inerrancy of Intent, not Fact

“Inerrancy is relative to the intent of the Scriptures, and this has to be hermeneutically determined” (Pinnock, SP, 225).

“All this means is that inerrancy is relative to the intention of the text. If it could be show that the chronicler inflates some of the numbers he uses for his didactic purpose, he would be completely within his rights and not at variance with inerrancy” (Pinnock, SP, 78)

“We will not have to panic when we meet some intractable difficulty. The Bible will seem reliable enough in terms of its soteric [saving] purpose,… In the end this is what the mass of evangelical believers need-not the rationalistic ideal of a perfect Book that is no more, but the trustworthiness of a Bible with truth where it counts, truth that is not so easily threatened by scholarly problems”(Pinnock, SP, 104-105).

The Bible is not the Word of God

“Barth was right to speak about a distance between the Word of God and the text of the Bible” (Pinnock, SP, 99).

“The Bible does not attempt to give the impression that it is flawless in historical or scientific ways. God uses writers with weaknesses and still teaches the truth of revelation through them” (Pinnock, SP, 99).

“What God aims to do through inspiration is to stir up faith in the gospel through the word of Scripture, which remains a human text beset by normal weaknesses [which includes errors]” (Pinnock, SP,100).

“A text that is word for word what God wanted in the first place might as well have been dictated, for all the room it leaves for human agency. This is the kind of thinking behind the militant inerrancy position. God is taken to be the Author of the Bible in such a way that he controlled the writers and every detail of what they wrote” (Pinnock, SP, 101).

The Bible is not Completely Infallible

“The Bible is not a book like the Koran, consisting of nothing but perfectly infallible propositions,… the Bible did not fall from heaven…. We place our trust ultimately in Jesus Christ, not in the Bible…. What the Scriptures do is to present a sound and reliable testimony [but not inerrant] to who he is and what God has done for us” (Pinnock, SP, 100).

He Rejects Warfield’s View of Inerrancy

“Inerrancy as Warfield understood it was a good deal more precise than the sort of reliability the Bible proposes. The Bible’s emphasis tends to be upon the saving truth of its message and its supreme profitability in the life of faith and discipleship” (Pinnock, SP, 75).

He Rejects ICBI View of Inerrancy

“Therefore, there are a large number of evangelicals in North America appearing to defend the total inerrancy of the Bible. The language they use seems absolute and uncompromising: `The authority of Scripture is inescapably impaired if this total divine inerrancy is in any way limited or disregarded, or made relative to a view of truth contrary to the Bible’s own’ (Chicago Statement, preamble). It sounds as if the slightest slip or flaw would bring down the whole house of authority. It seems as though we ought to defend the errorlessness of the Bible down to the last dot and tittle in order for it to be a viable religious authority” (Pinnock, SP, 127).

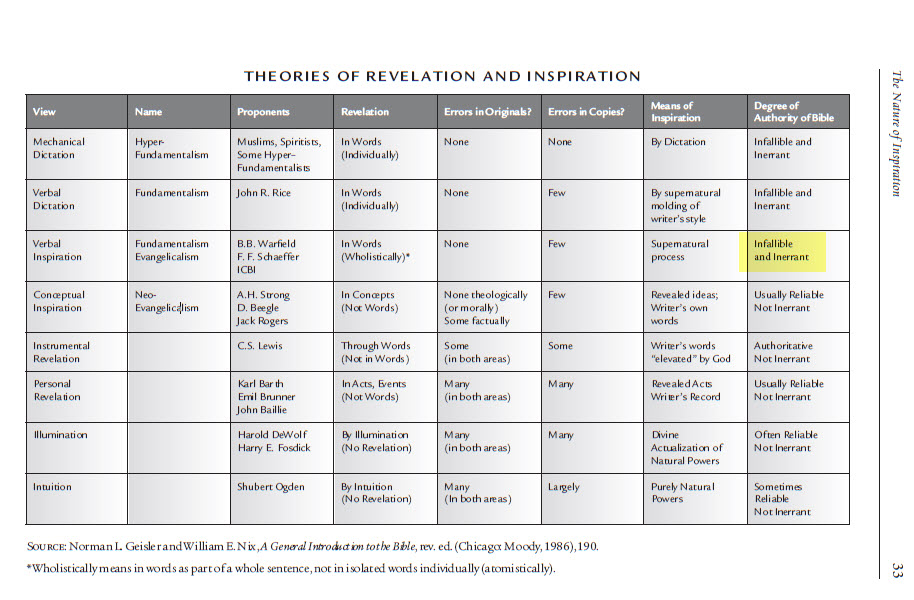

He Holds a Dynamic View of Inspiration, not Plenary Inspiration

“In relation to Scripture, we want to avoid both the idea that the Bible is the product of mere human genius and the idea it came about through mechanical dictation. The via media lies in the direction of a dynamic personal modelthat upholds both the divine initiative and the human response” (Pinnock, SP, 103).

“Inspiration should be seen as a dynamic work of God. In it, God does not decide every word that is used, one by one but works in the writers in such a way that they make full use of their own skills and vocabulary while giving expression to the divinely inspired message being communicated to them and through them” (Pinnock, SP, 105).

He Redefines Inerrancy and Rejects the Prophetic Model

“The wisest course to take would be to get on with defining inerrancy in relation to the purpose of the Bible and the phenomena it displays. When we do that, we will be surprised how open and permissive a term it is” (Pinnock, SP, 225).

“At times I have felt like rejecting biblical inerrancy because of the narrowness of definition [!! See previous quote] and the crudity of polemics that have accompanied the term. But in the end, I have had to bow to the wisdom that says we need to be unmistakably clear in our convictions about biblical authority, and in the North American context, at least, that means to employ strong language” (Pinnock, SP, 225).

“Paul J. Achtemeier has called attention to the inadequacy of the prophetic model for representing the biblical category of inspiration in its fullness-The Inspiration of Scripture: Problems and Proposals” (Pinnock, SP, 232, n. 8).

He Holds that there are Minor Errors in the Bible

“The authority of the Bible in faith and practice does not rule out the possibility of an occasionally uncertain text, differences in details as between the Gospels, a lack of precision in the chronology of events recorded in the Books of Kings and Chronicles, a prescientific description of the world, and the like” (Pinnock, SP, 104).

“What could truly falsify the Bible would have to be something that could falsify the gospel and Christianity as well. It would have to be a difficulty that would radically call into question the truth of Jesus and His message of good news. Discovering some point of chronology in Matthew that could not be reconciled with a parallel in Luke would certainly not be any such thing” (Pinnock, SP, 129).

“I recognize that the Bible does not make a technical inerrancy claim or go into the kind of detail associated with the term in the contemporary discussion. But I also see a solid basis for trusting the Scriptures in a more general sense in all that they teach and affirm, and I see real danger in giving the impression that the Bible errs in a significant way. Inerrancy is a metaphor for the determination to trust God’s Word completely” (Pinnock, SP, 224-225).

He Holds that The Bible Contains Myth and Legend

“In the narrative of the fall of Adam, there are numerous symbolic features (God molding man from dirt, the talking snake, God molding woman from Adam’s rib, symbolic trees, four major rivers from one garden, etc.), so that it is natural to ask whether this is not a meaningful narration that does not stick only to factual matters” (Pinnock, SP, 119).

“On the one hand, we cannot rule legend out a priori. It is, after all, a perfectly valid literary form, and we have to admit that it turns up in the Bible in at least some form. We referred already to Job’s reference to Leviathan and can mention also Jotham’s fable” (Pinnock, Sp, 121-122).

“Thus we are in a bind. Legends are possible in theory–there are apparent legends in the Bible–but we fear actually naming them as such lest we seem to deny the miraculous” (Pinnock, SP, 122).

“When we look at the Bible, it is clear that it is not radically mythical. The influence of myth is there in the Old Testament. The stories of creation and fall, of flood and the tower of Babel, are there in pagan texts and are worked over in Genesis from the angle of Israel’s knowledge of God, but the framework is no longer mythical” (Pinnock, SP, 123).

“We read of a coin turning up in a fish’s mouth and of the origin of the different languages of humankind. We hear about the magnificent exploits of Sampson and Elisha. We even see evidence of the duplication of miracle stories in the gospels. All of them are things that if we read them in some other book we would surely identify as legends” (Pinnock, Sp, 123).

He Holds Robert Gundry’s View of Midrash in Matthew

“There is no mythology to speak of in the New Testament. At most, there are fragments and suggestions of myth: for example, the strange allusion to the bodies of the saints being raised on Good Friday (Matt. 27:52) and the sick being healed through contact with pieces of cloth that had touched Paul’s body (Acts 19:11-12)” (Pinnock, SP, 124).

“There are cases in which the possibility of legend seems quite real. I mentioned the incident of the coin in the fish’s mouth (Matt. 17:24-27)…. The event is recorded only by Matthew and has the feel of a legendary feature”(Pinnock, SP, 125). [Yet Gundry was asked to resign from ETS by 74 percent of the membership.]

Pinnock on God

The Bible Has False Prophecy

“Second, some prophecies are conditional, leaving the future open, and, presumably, God’s knowledge of it” (Pinnock, MMM, 50).

“Third, there are imprecise prophetic forecasts based on present situations, as when Jesus predicts the fall of Jerusalem (Pinnock, MMM, 50).

“…despite Ezekiel, Nebuchadnezzar did not conquer the city of Tyre; despite the Baptist, Jesus did not cast the wicked into the fire; contrary to Paul, the second coming was not just around the corner (1 Thes. 4:17)” (Pinock, MMM, 51 n.66).

Even Jesus Made a False Prophecy

“…despite Jesus, in the destruction of the temple, some stones were left one on the other” (Mt. 24:2)” (Pinnock, MMM, 51 n.66).

God is not Bound to His Own Word

“God is free in the manner of fulfilling prophecy and is not bound to a script, even his own” (Pinnock, MMM, 51 n.66).

“We may not want to admit it but prophecies often go unfulfilled…” (Pinnock, MMM, 51, n.66).

God is Limited and Corporeal

“But, in a sense, creation was also an act of self-limitation…. Creating human beings who have true freedom is a self-restraining, self-humbling and self-sacrificing act on God’s part” (Pinnock, MMM, 31).

“As regards space, the Bible speaks of God having living space in the heavens:… Let’s not tilt overly to transcendence lest we miss the truth that God is with us in space” (Pinnock, MMM, 32).

“If he is with us in the world, if we are to take biblical metaphors seriously, is God in some way embodied? Critics will be quick to say that, although there are expressions of this idea in the Bible, they are not to be taken literally. But I do not believe that the idea is as foreign to the Bible’s view of God as we have assumed” (Pinnock, MMM, 33).

” The only persons we encounter are embodied persons and, if God is not embodied, it may prove difficult to understand how God is a person….Perhaps God uses the created order as a kind of body and exercises top-down causation upon it” (Pinnock, MMM, 34-35).

God’s Foreknowledge is Limited

“It is unsound to think of exhaustive foreknowledge, implying that every detail of the future is already decided” (Pinnock, MMM, 8).

“Though God knows all there is to know about the world, there are aspects about the future that even God does not know” (Pinnock, MMM, 32).

“Scripture makes a distinction with respect to the future; God is certain about some aspects of it and uncertain about other aspects” (Pinnock, MMM, 47).

“But no being, not even God, can know in advance precisely what free agents will do, even though he may predict it with great accuracy” (Pinnock, MMM, 100).

“God, in order to be omniscient, need not know the future in complete detail” (Pinnock, MMM, 100).

God Changes His Mind

“Divine repentance is an important biblical theme” (Pinnock, MMM, 43).

“Nevertheless, it appears that God is willing to change course…” (Pinnock, MMM, 43).

“Prayer is an activity that brings new possibilities into existence for God and us” (Pinnock, MMM, 46).

God is Dependent on Creatures

“According to the open view, God freely decided to be, in some respects, affected and conditioned by creatures…” (Pinnock, MMM, 5).

“In a sense God needs our love because he has freely chosen to be a lover and needs us because he has chosen to have reciprocal love…” (Pinnock, MMM, 30).

“The world is dependent on God but God has also, voluntarily, made himself dependent on it…. God is also affected by the world.” (Pinnock, MMM, 31).

God is not in Complete Control of the World

“This means that God is not now in complete control of the world…. things happen which God has not willed…. God’s plans at this point in history are not always fulfilled” (Pinnock, MMM, 36).

“Not everything that happens in the world happens for some reason,…. things that should not have happened, things that God did not want to happen. They occur because God goes in for real relationships and real partnerships” (Pinnock, MMM, 47).

“As Boyd puts it: ‘Only if God is the God of what might be and not only the God of what will be can we trust him to steer us…'” (Pinnock affirming Boyd, MMM, 103).

“Though God can bring good out of evil, it does not make evil itself good and does not even ensure that God will succeed in every case to bring good out of it” (Pinnock, MMM, 176).

“It does seem possible to read the text to be saying that God is an all-controlling absolute Being…. but how does the Spirit want us to read it? Which interpretation is right for the present circumstance? Which interpretation is timely? Only time will tell…” (Pinnock, MMM, 64).

God Undergoes Change

“For example, even though the Bible says repeatedly that God changes his mind and alters his course of action, conventional theists reject the metaphor and deny that such things are possible for God” (Pinnock, MMM, 63).

“I would say that God is unchangeable in changeable ways,…” (Pinnock, MMM, 85-86).

“On the other hand, being a person and not an abstraction, God changes in relation to creatures…. God changed when he became creator of the world… ” (Pinnock, MMM, 86).

“…accepting passibility may require the kind of doctrinal revisions which the open view is engaged in. If God is passible, then he is not, for example, unconditioned, immutable and atemporal” (Pinnock, MMM, 59, n.82).

He Admits Affinity with Process Theology

“The conventional package of attributes is tightly drawn. Tinkering with one or two of them will not help much” (Pinnock, MMM, 78).

“Candidly, I believe that conventional theists are influenced by Plato, who was a pagan, than I am by Whitehead, who was a Christian” (Pinnock, MMM, 143) [Yet Whitehead denied virtually all of the attributes of the God of orthodox theology, biblical inerrancy, and all the fundamentals of the Faith!!!]

All italic emphasis in original, bold emphasis this author’s emphasis.

SP–Clark Pinnock, The Scripture Principle (San Francisco, Harper & Rowe: 1984).

MMM–Clark Pinnock, The Most Moved Mover (Grand Rapids, Baker: 2001).

Did Clark Pinnock Recant His Errant Views?

By Norman L. Geisler

December 1, 2003

It Would Seem That He Did

It is widely believed that Clark Pinnock changed his views on whether the Bible has errors in it and thereby convinced the ETS Executive Council and Membership that his views were not incompatible with the inerrancy statement of the ICBI. As a result, both the Executive Council recommended and the membership voted on November 19, 2003 to retain him in membership.

It would seem that Pinnock did in fact recant his earlier view for several reasons. First, his restatement satisfied the Executive Committee who examined him. Second, his restatement convinced the membership of ETS who gave him a 67 percent vote of approval. Third, the paper he read at ETS left the impression that he had changed his view. Fourth, his written statement indicates that he made a “change.” Fifth, he wrote in his paper and said orally to the membership that he accepted the ICBI statement on inerrancy which would indicate a change. Finally, upon reading the Executive Committee report and hearing Pinnock’s paper, I too got the impression he had changed his view.

To cite the ETS Executive Committee about their decision, “This is a direct result of extensive discussion with Dr. Pinnock, including his clarifications of many points, and his clarifying and rewriting of a critical passage in his work, retracting certain language therein” (Letter October 24, 2003 from Executive Committee to ETS membership, p. 1, emphasis added in all quotes). They added, “The day ended with Dr. Pinnock disavowing– voluntarily and unprompted–some of the affirmations in note 66 [of Most Moved Mover which claimed that a number of biblical prophecies, including one by Jesus, were not fulfilled as predicted] (ibid., 3). Thus, “the Committee reveals its belief that, in the light of Dr. Pinnock’s clarifications and retraction of certain problematic language, the charges brought in November 2002 should not be sustained” (ibid., 3-4). They also said “Dr. Pinnock…has clarified and corrected parts of what he wrote” (“ETS Executive Committee Report on Clark H. Pinnock October 22, 2003,” p. 2).

On The Contrary

In spite of all of this, there is good evidence that Pinnock never really recanted his views on inerrancy. First, he never used the word “recant” of his views in either written or verbal form. Second, he never used any synonyms of recant when speaking of his views on this matter. Third, even if it could be shown that he actually changed his view on prophecy, he has never recanted his position on numerous other statements that are incompatible with the ETS statement on inerrancy.

When one reads carefully what the ETS Executive Committee said of their decision to approve of Pinnock’s views, it does not really say he recanted his views but only his way of expressing them. It wrote: “This is a direct result of extensive discussion with Dr. Pinnock, including his clarifications of many points, and his clarifying and rewriting of a critical passage in his work, retracting certain language therein” (Letter October 24, 2003 from Executive Committee to ETS membership, p. 1). Likewise, as we will see below, what Pinnock said was only a recantation of how he expressed his view, not of the view itself.

I Answer That

Once we understand Pinnock’s view, it is not difficult to explain why he appeared to change his view when in reality he did not. It grows out of his view of truth.

Pinnock’s Intentionalist View of Truth

When Pinnock speaks of the truth of Scripture, he does so in terms of the author’s intention. An error is what the author did not intend. Hence, an intended “truth” can actually be mistaken or not correct and still be “true” by Pinnock’s definition. This came out clearly in Pinnock’s answer to a question after his paper. When asked whether he would consider an inflated number in Chronicles an “error,” he responded, “No,” since exaggerating the numbers served the intention the author of Chronicles had in making his point. So, what is incorrect, mistaken, and does not correspond to reality, is not considered an “error.” Of course, by this intentionalist view of truth all sincere statements ever uttered, no matter how erroneous they were, must be considered true. Clearly, this is not what the ETS framers meant by inerrancy. Ironically, even the Executive Committee itself disavowed such a view in principle when they excluded “various forms of views explicitly affirming errors in the text (though condoned by appeals to so-called ‘authorial intent’).” See the “Executive Committee Report on John E. Sanders October 23, 2003,” p. 6. Unfortunately, they did not apply what they said to Pinnock himself.

That Clark Pinnock holds an intentionalist view of truth is clear from his many statements on the matter. He wrote, “All this means is that inerrancy is relative to the intention of the text. If it could be shown that the chronicler inflates some of the numbers he uses for his didactic purpose, he would be completely within his rights and not at variance with inerrancy” (Pinnock, The Scripture Principle (hereafter SP, 78). Again, “We will not have to panic when we meet some intractable difficulty. The Bible will seem reliable enough in terms of its soteric [saving] purpose…. In the end this is what the mass of evangelical believers need–not the rationalistic ideal of a perfect Book that is no more, but the trustworthiness of a Bible with truth where it counts, truth that is not so easily threatened by scholarly problems” (Pinnock, SP, 104-105). Finally, “Inerrancy is relative to the intent of the Scriptures, and this has to be hermeneutically determined” (Pinnock, SP, 225).

It is important to note that the ETS Constitution implies a correspondence view of truth when it speaks of one making “statements” that are “incompatible” with the Doctrinal Basis of the Society (Articles 4, Section 4). Further, even the Executive Committee affirmed a correspondence view of truth (“ETS Executive Committee Report on John E. Sanders Oct 23, 2003,” p. 2). But if this is so, then their action was inconsistent since on a correspondence view of truth Pinnock has unrecanted statements that claim the Bible affirms things that do not correspond to the facts (see below under nos. 4, 9, 10).

Pinnock’s Statement About ICBI is Misleading

Both in his paper and verbal presentation at ETS (11/19/03) Pinnock said he affirmed the ICBI statement on inerrancy. Many took this as an indication of his recanting. However, this is not the case since Pinnock is on record as viewing statements on “truth” as being what the author intended. But this is clearly not what they meant. But Pinnock seems unaware that the ICBI framers explicitly ruled this intentionalist view of truth out in favor of a correspondence view of truth. They wrote, “By biblical standards of truth and error is meant the view used both in the Bible and in everyday life, viz., a correspondence view of truth.” It adds, “This part of the article [13] is directed toward those who would redefine truth to relate merely to redemptive intent, the purely personal or the like, rather than to mean that which corresponds with reality.” It goes on to claim, contrary to Pinnock [SP. 119], that “the New Testament assertions about Adam, Moses, David and other Old Testament persons” are “literally and historically true” (R.C. Sproul, Explaining Inerrancy: A Commentary, Oakland, CA: ICBI, p. 31). But Pinnock clearly denied this (see no. 14 below).

So, Pinnock does not believe the ICBI statement on inerrancy which emphatically repudiates his view. In point of fact, Pinnock does to the ICBI statement what he does to the ETS statement; he reads them through his own intentionalist view of truth. In both cases, Pinnock is clearly in conflict with the meaning of the framers. On a correspondence view of truth, which is what the framers of both ETS and ICBI held, Pinnock’s view embraces errors in the Bible, that is, statements that do not correspond to the facts.

Further, Pinnock’s alleged recantation is not all encompassing. Pinnock did say that he was willing to make “changes” in his writings, but he did not tell us which ones. Indeed, he did not even say clearly that any of these changes would involve the admission of errors. He wrote: “I am 100% certain that, were we to sift through the text of The Scripture Principle as we did with the Most Moved Mover, some phrases would have to be improved on and some examples removed or modified.” Indeed, he added, “I am sure, were we to go through it carefully, changes would be in order” (“Open Theism and Biblical Inerrancy” a paper given on November 19, 2003 at the ETS annual meeting, p. 4). He spoke only of removing or modifying illustrations, improving phrases, and the like. There is not a single definitive word about admitting any error to say nothing of recanting four pages of quotations we presented the ICBI Executive Committee from Pinnock’s writings.

As to the ETS Executive Committee’s decision, a careful look at its language will reveal that Pinnock never recanted any of his views. Consider again the statements of the Committee. It speaks only of “clarifying and rewriting of a critical passage in his work, retracting certain language therein” (Letter October 24, 2003 from Executive Committee to ETS membership, p. 1). Notice that the only thing that was “retracted” was “certain language,” not his view. Indeed, Pinnock claims that his view remained the same, for he said, “I was not intending to violate it [the ETS inerrancy statement]. My clearing away the ambiguity is what made possible a positive verdict in my case. And I could do it sincerely since it had never been my intent to violate inerrancy here or elsewhere in my work” (Pinnock, ibid., 3). Pinnock said the same of statements he made in The Scripture Principle: “It was not and is not at all my intent to deny inerrancy…” (Ibid., 4). By this logic, no sincere author has ever made any error either in any of his or her books since they never intended to do so.

The Committee also said, “The day ended with Dr. Pinnock disavowing–voluntarily and unprompted–some of the affirmations in note 66 [of Most Moved Mover in which he claimed that a number of biblical prophecies, including one by Jesus, were never fulfilled] (October 24, 2003 letter from the ETS Committee to the membership, p. 3). Thus, “the Committee reveals its belief that, in the light of Dr. Pinnock’s clarifications and retraction of certain problematic language, the charges brought in November 2002 should not be sustained” (ibid., 3-4). But here again the only retraction was only of “problematic language,” not of his actual view on the matter which remains unrecanted.

The same is true of another use of the word “corrected” by the Committee with regard to Pinnock. They wrote: “Dr. Pinnock …has clarified and corrected parts of what he wrote” (“ETS Executive Committee Report on Clark H. Pinnock October 22, 2003,” p. 2). But here again it is not a correction of his view which was in error but of the language he “wrote,” that is, the way he expressed it.

Conclusion

In summation, although at first blush it would appear that Pinnock recanted all previously held views incompatible with the ETS inerrancy statement, the contrary evidence demonstrates that he did not recant any of these views. Certainly, he nowhere recants all of them. And even one of them is sufficient to show that he embraces a view that is incompatible with the ETS statement on inerrancy. Rather, using his intentionalist view of truth he claims he believes in inerrancy as understood by the ETS and ICBI framers, when in fact he does not.

But if Pinnock did not really recant his errant views, then what of the validity of the ETS acceptance of them as compatible with its inerrancy statement. It is bogus.

There is a way Pinnock can clear the air. All he has to do is to repudiate in unequivocal and unambiguous language all of the following statements he has made that are contrary to the ETS framers view of inerrancy:

1) “Barth was right to speak about a distance between the Word of God and the text of the Bible” (Pinnock, SP, 99).

2) “The Bible does not attempt to give the impression that it is flawless in historical or scientific ways” (Pinnock, SP, 99).

3) “The Bible is not a book like the Koran, consisting of nothing but perfectly infallible propositions…” (Pinnock, SP, 100).

4) “The authority of the Bible in faith and practice does not rule out the possibility of an occasionally uncertain text, differences in details as between the Gospels, a lack of precision in the chronology of events recorded in the Books of Kings and Chronicles…, and the like” (Pinnock, SP, 104).

5) “Did Jesus, teach the perfect errorlessness of the Scriptures? No, not in plain terms” (Pinnock, SP, 57).

6) “The New Testament does not teach a strict doctrine of inerrancy…. The fact is that inerrancy is a very flexible term in and of itself” (Pinnock, SP, 77).

7) “Why, then, do scholars insist that the Bible does claim total inerrancy? I can only answer for myself, as one who argued in this way a few years ago. I claimed that the Bible taught total inerrancy because I hoped that it did–I wanted it to” (Pinnock, SP, 58).

8) “For my part, to go beyond the biblical requirements to a strict position of total errorlessness only brings to the forefront the perplexing features of the Bible that no one can completely explain” (Pinnock, SP, 59).

9) “All this means is that inerrancy is relative to the intention of the text. If it could be shown that the chronicler inflates some of the numbers he uses for his didactic purpose, he would be completely within his rights and not at variance with inerrancy” (Pinnock, SP, 78).

10) “We will not have to panic when we meet some intractable difficulty. The Bible will seem reliable enough in terms of its soteric [saving] purpose…” (Pinnock, SP, 104-105).

11) “Inerrancy as Warfield understood it was a good deal more precise than the sort of reliability the Bible proposes. The Bible’s emphasis tends to be upon the saving truth of its message and its supreme profitability in the life of faith and discipleship” (Pinnock, SP, 75).

12) “The wisest course to take would be to get on with defining inerrancy in relation to the purpose of the Bible and the phenomena it displays. When we do that, we will be surprised how open and permissive a term it is” (Pinnock, SP, 225).

13) “Paul J. Achtemeier has called attention to the inadequacy of the prophetic model for representing the biblical category of inspiration in its fullness–The Inspiration of Scripture: Problems and Proposals” (Pinnock, SP, 232, n. 8).

14) “I recognize that the Bible does not make a technical inerrancy claim or go into the kind of detail associated with the term in the contemporary discussion…. Inerrancy is a metaphor for the determination to trust God’s Word completely” (Pinnock, SP, 224-225).

15) “In the narrative of the fall of Adam, there are numerous symbolic features (God molding man from dirt, the talking snake, God molding woman from Adam’s rib, symbolic trees, four major rivers from one garden, etc.), so that it is natural to ask whether this is not a meaningful narration that does not stick only to factual matters” (Pinnock, SP, 119).

16) “On the one hand, we cannot rule legend out a priori. It is, after all, a perfectly valid literary form, and we have to admit that it turns up in the Bible in at least some form. We referred already to Job’s reference to Leviathan and can mention also Jotham’s fable” (Pinnock, SP, 121-122).

17) “The influence of myth is there in the Old Testament. The stories of creation and fall, of flood and the tower of Babel, are there in pagan texts and are worked over in Genesis from the angle of Israel’s knowledge of God, but the framework is no longer mythical” (Pinnock, SP, 123).

18) “We read of a coin turning up in a fish’s mouth and of the origin of the different languages of humankind. We hear about the magnificent exploits of Sampson and Elisha. We even see evidence of the duplication of miracle stories in the gospels. All of them are things that if we read them in some other book we would surely identify as legends” (Pinnock, SP, 123).

19) “At most, [in the NT] there are fragments and suggestions of myth: for example, the strange allusion to the bodies of the saints being raised on Good Friday (Matt. 27:52) and the sick being healed through contact with pieces of cloth that had touched Paul’s body (Acts 19:11-12)” (Pinnock, SP, 124).

20) “There are cases in which the possibility of legend seems quite real. I mentioned the incident of the coin in the fish’s mouth (Matt. 17:24-27)…. The event is recorded only by Matthew and has the feel of a legendary feature” (Pinnock, SP, 125). [Yet Gundry was asked to resign from ETS by 74 percent of the membership.]

21) “God is free in the manner of fulfilling prophecy and is not bound to a script, even his own” (Pinnock, MMM, 51).

In short, the ETS framers would not affirm any of these and Pinnock has not denied any of them. If he really wants to clear the record, then all he has to do is deny all 21 of these in clear and unequivocal terms. If he does not, then his unrecanted written views are contrary to what the ETS statement really means since the framers would not agree with any of them. And it is an evangelical tragedy of great magnitude that the Executive Committee of ETS and a majority of its members have retained Pinnock in what has now become the formerly Evangelical Theological Society.

All italic emphasis in original, bold emphasis this author’s.

SP–Clark Pinnock, The Scripture Principle (San Francisco, Harper & Rowe: 1984).

MMM–Clark Pinnock, The Most Moved Mover (Grand Rapids, Baker: 2001).