The Crusades: Were they Justified? (2015)

The Crusades: Were they Justified?

Norman L. Geisler

2015

Recently president Barak Obama made a moral comparison between the Crusades and recent attacks and atrocities of the Radical Islamic group called ISIS, known for beheading, crucifying, and even burning its captives. Not only is there no moral equivalence between the actions of the Crusades and ISIS, this comparison reveals a serious lack of understanding of the Crusades.

The Prologue to the Crusades

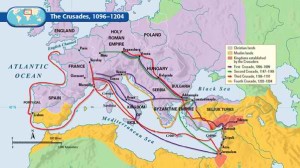

Between 1095 and 1400 there were some nine Crusades or expeditions of Western (European) Christians into the Eastern Mediterranean designed to recover the Holy Land from Muslim hands. These were encouraged by the Catholic Church and involved the death of thousands of people.

The Prologue to the Crusades: 500 Years of Muslim Advance

The Crusades can only properly be understood in terms of the 500 years of Muslim advance into the West that preceded them. Muhammad was born in A.D. 570 Mecca in present-day Saudi, Arabia. In 630 he led an army of 30,000 to conquer Mecca. By 711 Muslims took Syria, Iraq, Egypt and Jerusalem. By 732 they had invaded Spain and were turned back at Tours, France by Charles Martel. In 846 they attacked outlying areas of Rome. By the end of the 9th century Muslim pirates had established havens all along the Mediterranean coast, threatening commerce, communication, and pilgrim traffic for the next century. They controlled some 2/3 of Christendom. As a result, many Christians and Jews were enduring persecution at Muslim hands.

The Plea for the Crusades

By 1071 Eastern Christians sent appeals to the Western Christians for help. In 1095 Pope Urban II responded by calling on the Knights of Christendom to assist, and the first Crusade began what turned out to be a several hundred years of conflict.

The Purpose of the Crusades

Contrary to some modern secular charges, the Crusades were not colonial attempts to accumulate land and possessions. The primary purpose was spiritual. They wished to liberate the Christian captives from oppression by Muslims. Further, they desired to restore Christian access to the holy sites around Jerusalem. This is not to say that no unnecessary deaths and pillaging occurred. Regretfully, it did. However, the primary purposes were noble.

The Participants of the Crusades

The Crusaders consisted of Western Christians who loved their fellow believers in the East many of whom had lost their homes, land, and even their lives. This opens the door to address several widely held myths about the Crusades that call for a response.

Myth #1: The Crusades were wars of unprovoked aggression

against a peaceful Muslim world minding its own business.

The truth is that the Crusades were a reaction to 500 years of Muslim aggression into dominantly Christian countries. The Crusades were in essence a defensive action against the spread of Islam by the sword. They were undertaken largely out of concern for fellow Christians in the East. In fact, many great saints supported the Crusades, including Bernard of Clairvaux, Thomas Aquinas, and peace-loving Francis of Assisi. Troops prayed and fasted before battles and praised God after them. Even many Muslim respected the ideals of the Crusaders.

Of course, there were sins of overreactions by some Crusaders. But most of these were deeply regretted and forgiveness was sought by Christians who participated in them. Unfortunately, this was not so for Muslim exploiters who felt little remorse but looked to a future in Paradise as a reward for their endeavours in stomping out the infidels.

Myth # 2: The Crusades were colonialist imperialists after booty and land.

This charge is contrary to the facts of history. Most Crusaders undertook the 2000 mile trek at great sacrifice of their own wealth. Many sold or mortgaged their own homes, most of which were not recouped. Most never occupied the land they gained from the Muslims. They went out with a sense of duty to God.

Myth # 3: When the crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099,

they massacred ruthlessly.

This criticism is overstated. Of course, people were killed, but it was not ruthless. It was usually in accord with the norms of war for that time. Cities that resisted were captured and subjugated to the captors, but inhabitants of cities that surrendered were not killed. However, the people who surrendered most often retained their property and worshiped freely (see SALVO, issue 27 [Winter, 2013], pp. 60-62).

The Perversion of the Crusades

If this is so, then why do most people today have a distorted view of the Crusades? It was not always so. During the Middle Ages nearly all Christians in Europe believed the Crusades were morally justified. The modern distortion of the Crusades began with French humanist Voltaire (1694-1778) who abhorred Christianity (see his Philosophical Dictionary). The contemporary anti-crusade stance was set by Sir Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades (1951-1954) and popularized by a BBC/A&E documentary (1995).

Only recently has this negative attitude begun to be corrected. Professor Rodney Stark is a case in point. He wrote, “Not only had the Byzantines lost most of their empire; the enemy was at their gates.” Hence, “the popes, like most Christians, believed war against the Muslims to be justified partly because the latter had usurped by force lands which once belonged to Christians and partly because they abused the Christians over whom they ruled and such Christian lands as they could raid for slaves, plunder and the joys of destruction” (Rodney Stark, God’s Battalions: The Case for the Crusades (HarperOne, 2009), pp. 33, 248) Other authors have added to this re-evaluation of the Crusades (see also Thomas F. Madden, The New Concise History of the Crusades, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. 2005).

Dr. Geisler is a philosopher, theologian, and ethicist who has authored two books devoted to the subject of ethics: The Christian Love Ethic (Bastion Books: 2012) and Christian Ethics: Contemporary Issues and Options (Baker Academic:1989, 2010)